Home > International > Kojirakawa international Center > Japanese language and culture (Kojirakawa campus) > Japanese culture course > An Introduction to Japanese Culture I (Spring)

This course utilizes local resources in Yamagata for students to experience aspects of the Japanese culture such as the Dressing Kimono, Participate in the Hanakasa Festival, Nannkinn tamasudare (Japanese traditional street Art) , Baking pottery, Zazen meditation, Japanese traditional music (bamboo flute and mukuri), Kendama, and a Hot spring, through an environment rich in traditional culture and nature in Yamagata. On occasion, specialists from outside the university are invited as a lecturer.

The aim of this course is to provide international students an opportunity to improve their proficiency in Japanese and to deepen their understanding of the Japanese culture and society. This course is offered in Spring Semester. The class meets once a week.

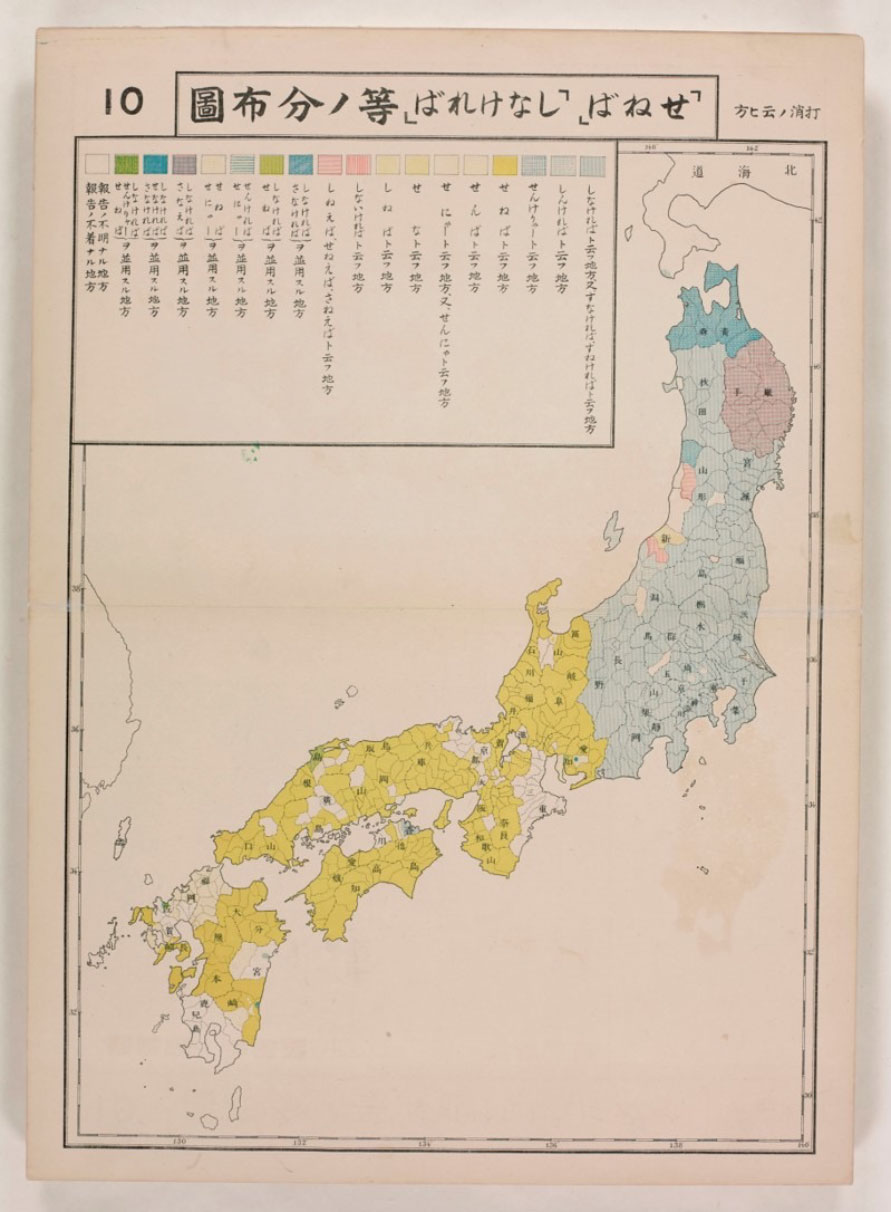

Students will be introduced to elements of socio-linguistics, i.e. the effects of culture on language, with a focus on dialectology and a close look at some of the various dialects that can be found not only in Japan but also around the world. Students will be asked to do an individual or group final class presentation on a dialect of their own language and as such group work outside class will be required. The goal of this class is to gain a better understanding of one’s own linguistic identity.

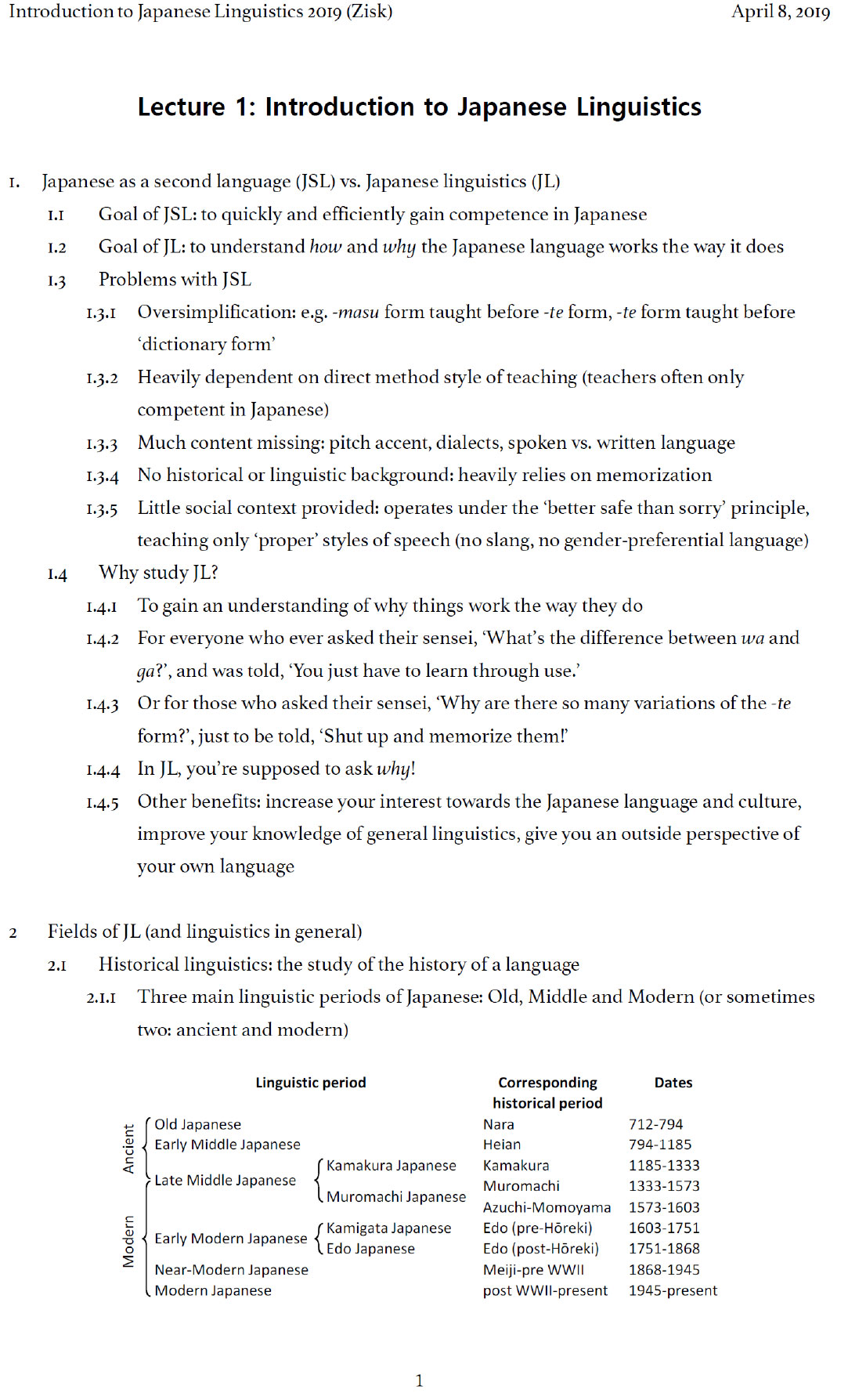

The goal of this class is to give you a basic understanding of how the Japanese language functions from a linguistic perspective. Topics include the origin of the Japanese language, Japanese phonology, the Japanese writing system, grammar, sociolinguistics and language contact, dialects and government language policy.

Grades will be based on a combination of class participation and a take-home final exam.

A comparative look at some interests Japanese follow after they finish their 9-5. The course will cover the histories of various pastimes popular in Japan, paying special attention to the gaming and gambling side of Japanese entertainment. There will be a hands-on approach to the final part of each week and classes will be made as interactive as possible.

Japanese Popular Heroes, from the Age of Wars to Pre-modern Days

From Japan’s legendary past to the advent of modern times a hundred and forty years ago, there have been a number of persons, either historical or fictional, who have become as famous as to represent their respective age. These keep reappearing again and again in novels, films, and on television. Closely linked to these are a small number of stereotypes everybody knows: samurai, yakuza, etc. Virtually all of these heroes stem from the warrior class; but they differ very much from one another with respect to their status and personality, and the age they were living in. This class will show some typical films centering on representative heroes from the Kamakura Age to the end of the Edo Era. We will see how, within three hundred years of times getting first more and more peaceful and then more and more chaotic, the image of the typical hero changed from warlord to politician to avenger (Chushingura) to complete outlaw (Shimizu no Jirocho, Kunisada Chuji): from ruling representative of the country to respectable gangster. All of these heroes are still present in the public mind now, their images being highly contradictory and quite fascinating.

○独眼竜政宗

Masamune, the One-Eyed Dragon (1959, aka Hawk of the North)

Production Company: Toei Kyoto

Director: Kono Toshikazu河野寿一(1921-1984)

Writer: Takaiwa Hajime高岩肇(1910-2000)

Certainly the most famous historical figure associated specifically with Northern Japan is Date Masamune伊達政宗(1567-1636). As with other warlords, his figure as represented in historical fiction, films, and on television has been made palatable for popular tastes, but even so his profile stands out. First, as a fierce young warrior of fearsome appearance, having lost one eye through smallpox and donning a black-and-gold armour: succeeding his retiring father as daimyo at the age of eighteen (of an area now belonging to Fukushima Prefecture), he soon won all surrounding provinces including those held by relatives through attacks, though having to kill both his father and his brother in the course. Then, in the 1590s, as Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s chief ally during his last years: Hideyoshi being, after Nobunaga’s death, the most powerful man in Japan, Masamune had no choice but to participate in the Korean invasion of 1593. Thirdly, as lord of the Sendai domain, since 1604: joining Tokugawa Ieyasu after Hideyoshi’s death (1598), and given this profitable domain in due course, he became one of the most powerful daimyo in Japan. Lastly, as a man of higher ethics than most other Sengoku warlords, including strong loyalty towards Hideyoshi and Ieyasu, neither of whom trusted him completely, and a tolerant attitude towards Christian religion, which had been declared illegal by Ieyasu.

Kono Toshikazu, creator of a new style in historical films in the 1950s, and writer Takaiwa, who had been equally adept at modern subjects including literary adaptations, draw mostly on the first two of these images, whereas nowadays the third seems to be dominant. Along with the leading young jidaigeki star of his day, Nakamura (later Yorozuya萬屋) Kinnosuke中村錦之助, the two great old-timers Tsukigata Ryunosuke月形龍之介and Okochi Denjiro大河内傳次郎(1898-1962) can be seen as Masamune’s father and old Kansuke, respectively.

○水戸黄門Mito Komon (1960)

Production Company: Toei

Director: Matsuda Sadatsugu松田定次(1906-2003)

Writer: Oguni Hideo小国英雄(1904-1996)

Many historic personalities have been fictionalized posthumously, and turned into adventurous existences. This was one way Japanese history was made attractive for later ages; it manifested itself in popular story-telling and, later, popular fiction. In the case of Tokugawa Mitsukuni徳川光圀(1628-1701), a grandson of Ieyasu, and an influential scholar and politician in his own right, a 19th century tale about his adventurous travels around Japan started the fashion. It was followed by novels, films, and since 1951, television series, making him one of the most durable heroes of the Edo period; indeed, the most popular figure between the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate and the Chushingura events of 1701. Certain historical facts and events of his lifetime are used as background in all of these tales; in this case, the Edo fires of 1691 and the opposition against the Tokugawa Shogunate, which, widespread as it was among masterless samurai, had already led to the rebellion led by Yui Shosetsu由比正雪(1605-1651).

The greatest of all Mito Komon on screen was Tsukigata Ryunosuke月形龍之介, who in this film is supported by numerous guest stars like Kataoka Chiezo片岡千恵蔵, Ichikawa Utaemon市川右太衛門, Nakamura Kinnosuke中村錦之助, Okawa Hashizo大川橋蔵, and Otomo Ryutaro大友柳太朗. His omnipresent helpers Suke-san and Kaku-san are played by Azuma Chiyonosuke東千代之助 and Kinnosuke’s brother Nakamura Katsuo中村賀津雄. Director Matsuda Sadatsugu, son of the first historical-film maker in Japan, Makino Shozo, was one of the leading directors of lavish entertainment from the late 1920s through the mid-Sixties. Aomori-born screenwriter Oguni Hideo, successful in both contemporary and historical pieces since the mid-Thirties, is probably best known as Kurosawa Akira’s most frequent script collaborator, including Ikiru, The Seven Samurai, Yojinbo, Red Beard, Dodesukaden, and Ran.

The last years before the Second World War were both a highly interesting and a very confusing time in Japan: high unemployment and growing distance between government and people on one hand, rapid developments in most arts, including one of the most interesting national film cultures, and remarkable literary activity, albeit under censorship, on the other. This class will focus on the fifteen first years of Showa history, 1926 to 1941, by showing classic films of the period and reading some of its stories, all depicting important aspects of their day. The class aims at giving a vivid picture of life in Japan during the most turbulent and complicated period of its modern history: the last days of peace, with all their problems.

Along with a minimum of commentary and explanation, we are going to watch some of the most acclaimed films of their day (with subtitles), read some short works by major writers (English translation attached), and will have enough chance to ask or discuss afterwards. Note that the following list of films and stories need not be the exact contents of this class: along with questions and/or further discussion of points of interest, wishes for others will be eagerly appreciated.

○稲妻Lightning (1952)

From a novel by Hayashi Fumiko林芙美子(1903-1951/1936)

This story of a large, unhappy working-class family was one of Hayashi Fumiko’s chief long novels. Originally published in the mid-Thirties, when the mental and financial strains of everyday life were already frequently depicted in fiction and less often in films, its situation has here been changed successfully into postwar Tokyo, where an aging mother and her adult children, three daughters and one son of vastly different characters since they are all from different fathers, try to make ends meet somehow, with dubious success in spite of much quarrel and confusion. The main character of the youngest daughter, unmarried and working as a bus guide, is played by Takamine Hideko高峰秀子(1924-2010), her weak elder sister by Miura Mitsuko三浦光子(1917-1969), with many other familiar faces of postwar Japanese cinema in support. It was the second of six Hayashi films by director Naruse Mikio成瀬巳喜男(1906-1969).

○何が彼女をそうさせたか

What Made Her Do So? (1929)

Production Company: Teikine (Teikoku Kinema)帝国キネマ

Director-Writer: Suzuki Shigeyoshi (Jukichi)鈴木重吉 (1900-1993)

Original Drama by Fujimori Seikichi藤森成吉(1892-1977)

The original appeared in 1927, was soon successful, and filmed two years later. Born and raised in Nagano Prefecture, the author was very active politically, even sent to prison for this in the Thirties, but actually came from a rather well-to-do family, and only had his first-hand working class life experience from age thirty. On its first screening in Osaka and Tokyo, in early February, 1930, this film became the biggest hit the Japanese silent picture ever had, with a long run of five weeks. It was voted Best Modern Film of 1930 (as opposed to Historical Film) by the leading film magazine, Kinema junpoキネマ旬報.

Inspired by poor living and working conditions in Japan at the time, left-wing tendency dramas like this one were generally scoring huge successes during the late Twenties, so the motion picture industry – big companies with a varied output like Shochiku or Nikkatsu as well as studios usually confining themselves to pure entertainment like Teikine – was fast in producing so-called ‘tendency films’傾向映画. These films usually dealt with ordinary people battling some tough fate in contemporary Japan. As can be seen from this film’s financial success, it isn’t just forwarding some political message but had a strong mass appeal as well, in spite of its strictly rural setting. Different from Western countries, dark and tragic stories were generally more popular than comedies at the time.

Most Japanese films of the period up to 1945 having been wholly or partly lost during the wartime, this one, too, only exists in an incomplete print, with more than one third missing, including the final scene (!).