Home > International > Kojirakawa international Center > Japanese language and culture (Kojirakawa campus) > Japanese culture course > An Introduction to Japanese Culture Ⅱ (Fall)

This course utilizes local resources in Yamagata for students to experience aspects of the Japanese culture such as the Kimono, Tea ceremony, Flower arrangement, Making traditional confections (Wagashi) & Kokeshi doll, Folding paper (Origami), Zen meditation, Visit historical museum, Japanese traditional music (bamboo flute) through an environment rich in traditional culture and nature in Yamagata. On occasion, specialists from outside the university are invited as a lecturer.

The aim of this course is to provide international students an opportunity to improve their proficiency in Japanese and to deepen their understanding of the Japanese culture and society. This course is offered in autumn Semester. The class meets once a week.

▲Field trip

Bunshokan (The Former Prefectural Office and Assembly Building)

▲Field trip

Yamadera (Risshaku-ji Temple)

▲Chery blossom viewing

▲Ikebana (Flower arrangement)

Students will be introduced to elements of modern Japanese society with a focus on daily life and some of the issues that Japan will have to face in the near future. Students will be asked to do an individual or group class presentation on a topic of Japanese society of their own choosing and as such work outside class will be required. The goal of this class is to gain a broader understanding of contemporary Japan.

Some parts of Japanese history have become so popular that you can feel it even now: either whole epochs, like the Sengoku age, the latter part of the Edo era (Bakumatsu), or early to mid-Meiji, i.e. the time before 1900; or the lives of popular lions like Oda Nobunaga or Tokugawa Mitsukuni (Mito Komon); or just single episodes of revenge and bravery. Popular stage and later screen have capitalized on this for a long time. Don’t forget many Kabuki classics were using scandals of the day as their plot. Let’s have a look at some of these episodes as depicted in more-or-less lavish film adaptations. We won’t only see some of Japanese history, but also Japanese popular tastes of the 20th Century. The films are quite different from Western historical adventure yarns, so this class can be counted on to be both enjoyable and instructive.

Rather than handing in a written report, participants are expected to prepare a short English-speaking presentation on a course-related topic of their own choice along with an accompanying handout for one of the final sessions.

○忍術御前試合Royal Tournament of Ninja, aka Toriwakamaru, the Koga Ninja (1957)

Production Company: Toei東映

Director: Sawashima Tadashi沢島忠(1926-2018)

Writer: Ogawa Tadashi小川正(1906-?)

What made the final stages of the Sengoku age so popular with audiences was both the presence of several impressive warlords at once and the overall richness of action in their rivalries. During the Fifties, adapting popular history for a juvenile audience was not uncommon at all; many of these pieces were written by Ogawa Tadashi. This picture is typical of that fashion: it involves spy activities of Ninja in the service of Tokugawa Ieyasu徳川家康(1542-1616) and Toyotomi Hideyoshi豊臣秀吉(1534-1598) fighting for Osaka Castle, as well as the most famous Japanese robber, Ishikawa Goemon石川五右衛門(d.1594), here played by character villain Tomita Nakajiro富田仲次郎(1911-1990). The film marked the debut of one of the most acclaimed postwar jidaigeki directors, Sawashima Tadashi沢島忠. Apart from several young stars of the day, the cast includes three great veterans: Okochi Denjiro大河内伝次郎(1898-1962) as Hideyoshi, former jidaigeki director Ikeda Tomiyasu池田冨保(1892-1968, under the name of Mochizuki Kensuke望月健祐) as Ieyasu, and Tsukigata Ryunosuke月形龍之介(1902-1970) as the great Ninja Momochi Sandayu百地三太夫(1512-1581).

○血槍無双The Best Spear Fighter, aka Blooded Spear (1959)

Production Company: Toei

Director: Sasaki Yasushi佐々木康(1908-1993)

Writer: Oguni Hideo小国英雄

One of the most popular episodes within Japanese history were the events related to the forty-seven samurai left without a master when Asano Takumi-no-kami浅野内匠頭(1667-1701) was sentenced to death, and their revenge for him two years later. This strictly illegal action was certainly no stage matter officially approved of; rather, it is one example of how scandals of the day sold well and long within the popular culture of Edo, how far the stage could go too far even then, and how popular taste turned away from the Shogunate. The straight story alone, involving huge numbers of characters, did not only become a great stage success since mid-18th Century as both Bunraku and Kabuki plays, but also the most often-filmed historical subject by far. Apart from this main tale – called mostly Chushingura忠臣蔵, The Faithful Vassals, and sometimes after the war Ako roshi赤穂浪士, The Masterless Samurai of Ako Castle –, many side-stories related to the people involved have appeared as plays, novels, and films, most of them involving completely fictitious characters and episodes. This one, about an aging spear fighter appointed to train one of the Asano warriors, came from 19th Century storytelling and had already been adapted for the Kabuki stage by Kimura Kinka木村錦花(1877-1960). In this film, the (fictitious) central character Tawaraboshi Genba俵星玄番is played by veteran star Kataoka Chiezo片岡千恵蔵(1903-1983), his trainee Sugino Juheiji杉野十平次(1676-1703) by Okawa Hashizo大川橋蔵(1929-1984), and Oishi Kuranosuke大石内蔵助(1659-1703), mastermind behind the revenge and leading person of the ‘straight’ Chushingura, by Okochi Denjiro大河内伝次郎(1898-1962). Chushingura versions invariably had a grand supporting cast; this one includes Wakayama Tomisaburo若山富三郎(1929-1992) as Takebayashi Tadashichi武林唯七(1672-1703) and Kurokawa Yataro黒川弥太郎(1910-1984) as Horibe Yasubee堀部安兵衛(1670-1703). Director Sasaki Yasushi, comparative newcomer to historical subjects, had nevertheless become one of Toei’s most successful directors. This mood piece is one of his most highly-acclaimed films.

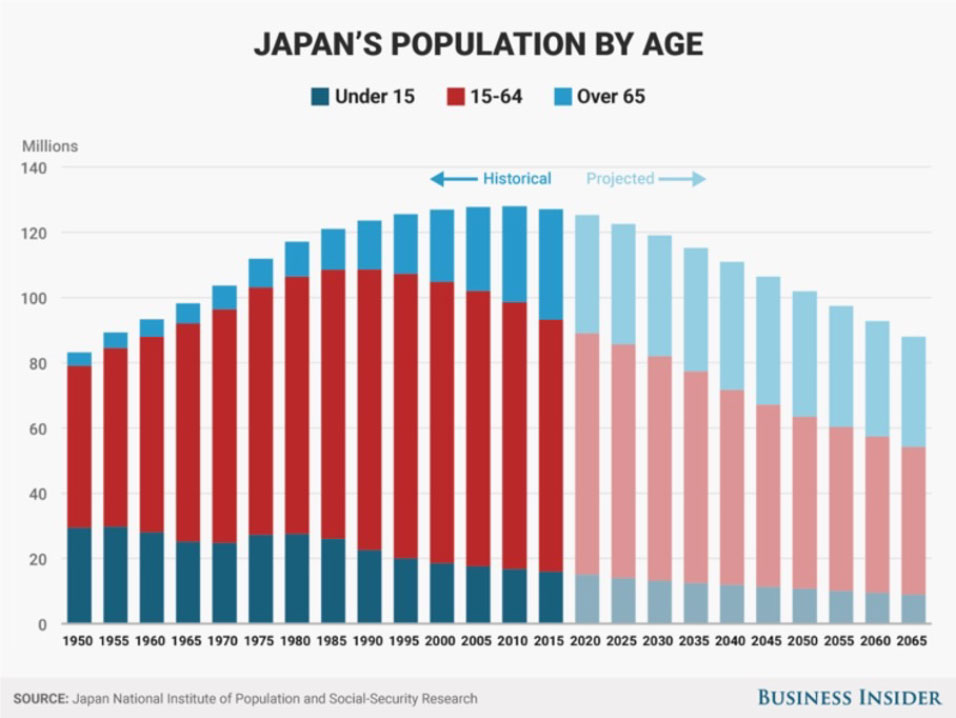

This course will give a lecture about the Japanese rites of passage. Since the depopulation and aging of this society is a serious concern in Japan, the way of rites of passage had been transformed. Under the background of Japanese society, this lecture will discuss the changing procedures of the rites of passage in both of Japanese cities and villages . In addition, social problems will also be examined and discussed.

▲The ceremony for long life

▲The ceremony for unlucky age

▲First seasonal ceremony for new-born baby(Doll’s Festival)

Experience the artistic way of writing Japanese language : Kanji (Chinese

characters), Katakana, Kana

make a presentation of your own work by using basic techniques of this art

Let’s enjoy Shodo, one of the essential parts of Japanese culture.

As a sequel to my course on pre-WWII Japan, this class will give an easy introduction to what Japanese life has been like during the first decades after the war: a modern country re-emerging from the worst destruction in its history into some of its most culturally satisfying decades ever. This was the period between pre-war society and the Japan we know today. Its rapid changes, the building-up of a new society, and many characteristics of these new times have been depicted in both novels and films. Of course, time space will be all too limited to give a full over-view; anyhow, students of this course will be offered at least some glimpses of the formative years of post-war Japan. We are going to watch some major Japanese films (in English-subtitled versions), and read some representative stories of the period from the first two decades after the war (English translations attached), along with a minimum of commentary and explanation, and have enough chance to ask or discuss afterwards. Note that the following list of films need not be the exact contents of this class: along with questions and/or further discussion of points of interest, wishes for other pictures will be eagerly appreciated.

○女が階段を上がる時

When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (1960)

Production Company: Toho東宝

Director: Naruse Mikio成瀬巳喜男(1906-1969)

Screenplay: Kikushima Ryuzo菊島隆三(1914-1989)

The combined work of Naruse, a master of literary adaptations famous since the mid-Thirties, and post-war screenwriter Kikushima, who also produced this picture, made it a hit in 1960. The director’s style compasses both an overall bleak realism and a keen eye for fashionable chic. Depicting contemporary women’s characters was his main forte, while this was quite new for the writer, who is best known for some Kurosawa and sports film scripts. Eventually, both were very much able to fill this piece about a bar in the fashionable Ginza district with a lot of descriptions both of people working there and the well-to-do guests they entertain. In Japanese life and literature, amusement and after-work relaxation has long been a frequent topic, so bars appear, more or less prominently, in innumerable books and films; but hardly anywhere has the everyday life typical of these environments been shown in more detail, and with more sympathy, than in this film. Though shot in black-and-white, many famous actors of the day can be seen among both hostesses and customers: Takamine Hideko高峰秀子(1924-2011), who designed the costumes, too, as the somewhat reluctant bar madam, Nakadai Tatsuya仲代達矢(1932-) as her right hand, Awaji Keiko淡路恵子(1933-2014) as an ambitious hostess, Mori Masayuki森雅之(1911-1973) as a banker, Kato Daisuke加東大介 (1911-1975), Ozawa Eitaro小沢栄太郎(1909-1988) and the great Kabuki actor Nakamura Ganjiro中村鴈治郎(1902-1983) as guests eager to win the madam’s sympathies.

○武士道残酷物語

Cruel Tales of the Warrior’s Way (1963)

Production Company: Toei

Director: Imai Tadashi今井正(1912-1991)

Writers: Suzuki Naoyuki鈴木尚之(1929-2005), Yoda Yoshikata依田義賢(1909-1991)

Original Novel by Nanjo Norio南条範夫(1908-2004, 1959)

One thing that changed significantly after the war was the official way of looking at the past, from the earliest myths to WWII. Glorifying both national spirit and the various wars it had led to – wars that had both unified Japan and torn it apart at the same time – had been almost a matter of common sense before, whereas now, all of a sudden, all forms of the state apart from the present democracy were considered more or less oppressive and inhuman. Leftist ideologies had been gaining much ground and won a lot of sympathies during the hard times before the war, and were more and more outspoken after 1945, particularly after the occupation had officially ended in 1952. By the early Sixties, descriptions of the past in general as inglorious were already acceptable within the mainstream. Moreover, general audiences already preferred realistic action in both historical and contemporary context over mere swashbuckling: within popular culture, violence became more and more of an attraction.

Being a sequence of seven tragic stories through various ages within the warrior family Iikura, this film offers a rare mix of historical and contemporary elements: made by the leading Japanese director of ‘socialist realism’ for the most successful historical entertainment production, and adapted by two contrasting writers from a prize-winning story by an extremely prolific postwar economist-writer known for historical novels, it features many typical jidaigeki veterans along with modern faces like Kimura Isao木村功(1923-1981), Arima Ineko有馬稲子(1932-), Mori Masayuki森雅之(1911-1973), Kishida Kyoko岸田今日子(1930-2006), and Sato Kei佐藤慶(1928-2010), and has the greatest star of historical adventure to emerge after the war, Nakamura Kinnosuke中村錦之助(1932-1997), in all seven leading parts.